“Charming… Aimée is one of those blithe spirits who can walk you through the city’s historical streets and byways with their eyes closed.”

—Marilyn Stasio, The New York Times Book Review

“Leduc has a thorough grasp of the practicalities of investigation, plus a penchant for undercover work that will have readers on pins and needles.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

Buy it: IndieBound.com | PoisonedPen.com | Amazon.com | BN.com | Powells.com | Politics & Prose | Book Passage | Soho Press

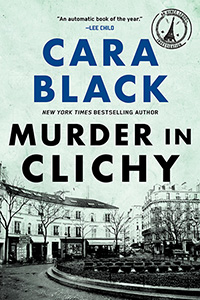

Aimée has been introduced to the Cao Dai temple in Paris by her partner René. He urges her to learn to meditate: she could use a more healthful approach to life. The Vietnamese nun Linh has been helping Aimée to attain her goal, so when she asks Aimée for a favor—to go to the Clichy quartier to exchange an envelope for a package—René prompts Aimée to agree. But the intended recipient, Thadée Baret, is shot and dies in Aimée’s arms before the transaction can be completed, leaving Aimée with a wounded arm, a check for 50,000 francs, and a trove of ancient jade artifacts. Whoever killed Baret wants the jade. The RG—the French secret service—a group of veterans of the war in Indochina and some wealthy ex-colonials and international corporations seeking oil rights are all implicated. And the nun, Linh, has disappeared.

Excerpt

Tuesday

In the storefront Cao Dai temple under the red lanterns, her foot asleep, pins and needles up and down her legs, Aimée Leduc struggled to keep her spine straight, thumb and pinky together, in the half-lotus position. Her partner René, a dwarf, sat with a look of total concentration, in perfect Lotus posture, in the men’s section. But Aimée’s brain flashed with lines of computer code and throbbed with an ache for an espresso. No blank slate of tranquility for her with sirens hee-hawing on the quai and the Seine fog curling over the skylight. As the blue-robed priest struck the gong, the sigh of relief she exhaled mingled with the mindful breaths and musk of incense surrounding her.

“Three weeks, René,” she muttered, “and I still can’t meditate!”

She’d tried and failed breathing exercises, a new practice she’d begun with René Friant, her business partner, after her optic nerve had been damaged the previous month during an assault. It had seemed like a good time to begin to live healthily.

The ten or eleven women in yoga pants, from the nearby Université de Paris, grabbed their books and headed for the door. Ripe fruit scents from the tiered altar offerings clung to the velvet curtains that kept out the cold. The swish of a broom wielded by Quoc, the temple custodian, an older Vietnamese man, filled the foyer.

“Mindfulness,” René said, rolling up his meditation mat, “think of it like that. Try to concentrate. Don’t give up, Aimée.”

René was right, of course. But the calmness and tranquility she sought remained as elusive as a wisp of smoke, even though her bouts of blurry vision had receded. She had her sight now, most of the time.

From the rear came Linh, a slender Vietnamese nun, in a Mandarin collared white ao dai tunic with matching trousers, smiling, her palms together in greeting. Middle-aged, her black hair in a bun, crows feet lines fanned from her eyes as she smiled.

“Forgive me, we’ve worked on this before,” Linh said, an undertone of sibilance just perceptible in her accented French. “Next time, Aimée, be open to the divining board; that’s a form of meditation.”

Like a large wooden ouija board, the divining board stood near the all-seeing divine eye, the Cao Dai’s symbol, a huge globelike eyeball suspended over the altar. Mediums used it to communicate with the spirit world in seances and in prayers to a pantheon of divine beings, including the Buddha, Confucius, Lao Tzu, and Jesus Christ. Crystal candelabras, brass drum bowls, yin and yang symbols, and peacock feathers adorned side altars.

“Merci, Linh,” she said, grateful for help from the nun she’d met only last week.

Pictures of Victor Hugo and Sun Yat-sen lined the walls. They were venerated as saints in this esoteric sect, whose philosophy was a potpourri of Hinduism, Christianity, Taoism, Islam, and Buddhism. A sign reading VAN GIAO NHAT LY, meaning “All religions have the same reason,” faced her. Aimée inhaled the peacefulness of the small, makeshift temple, wishing that tranquility would stay with her.