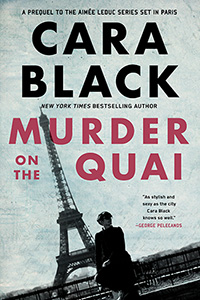

“Who wouldn’t love to catch a glimpse of a favorite sleuth as a blundering amateur? Cara Black lets us do just that in Murder on the Quai, which reveals how Aimée Leduc, her fashionable Parisian private investigator, joined the business founded by her father and grandfather… The case is engrossing, complete with Vichy flashbacks, but the most fun are the scenes where Aimée meets her future partners and acquires Miles Davis, her beloved bichon frisé.”

—Marilyn Stasio, The New York Times Book Review

“This vivid prequel… alternates between Aimée’s investigation and violent events in November 1942 in a small village in Vichy France that may be at the root of several killings. As Aimée becomes a target and her father’s trip grows complicated, Black reveals why Aimee chooses to pursue the family business.”

—BBC

Buy it: IndieBound.com | PoisonedPen.com | Amazon.com | BN.com | iBooks | Kobo.com | Powells.com | Politics & Prose | Book Passage

November 1989: Aimée Leduc is in her first year of college at Paris’s preeminent medical school. She lives in a 17th-century apartment that overlooks the Seine with her father, who runs the family detective agency. But the week the Berlin Wall crumbles, so does Aimée’s life as she knows it. First, someone has sabotaged her lab work, putting her at risk of failing out of the program. Then, she finds out her aristo boyfriend is planning to get engaged to another woman. And finally, Aimée’s father takes off to Berlin on a mysterious errand. He asks Aimée to help out at the detective agency while he’s gone—as if she doesn’t already have enough to do. But the case Aimée finds herself investigating—a murder linked to a transport truck of Nazi gold that disappeared in the French countryside during the height of World War II—has gotten under her skin. Her heart may not lie in medicine after all—maybe it’s time to think harder about the family business.

Excerpt

Paris · November 9, 1989 · Thursday Night

Standing outside the Michelin-starred restaurant, a stone’s throw from the Champs-Élysées, the old man patted his stomach. The dark glass dome of the Grand Palais loomed ahead over the bare-branched trees. To his right, the circular nineteenth-century Théâtre Marigny.

“Non, non, if I don’t walk home I’ll regret it tomorrow.” He waved off his two drunken friends, men he’d known since his childhood in the village, as they laughingly fell into a taxi. Course had followed course; remembering the caviar-dotted lobster in a rich velouté sauce topped off by Courvoisier brandy, he rubbed his stomach again as he waved goodnight to the departing taxi. His belly was taut with discomfort; he needed to stretch it out before bed. Besides, he always enjoyed the walk home to his place on Place François Premier. Even now, after all these years, pride swelled in his chest that he had secured himself an address in le triangle d’or, the golden triangle, the most exclusive quartier in Paris. The thrill of living among the mansions and hôtels de luxe between avenues Montaigne, George V, and the Champs-Élysées never got old to him.

He looped his silk scarf tight, took a deep breath of the piercing chill November night. Belched. The born farmer in him sensed tonight would bring frost—a crinkled frost that would melt on the grey cobbles like tears. In the village, it would have been a hoarfrost blanketing the earth like lace.

He looked over his shoulder—force of habit—with vigilance that hadn’t diminished in forty years. They were always so careful, so scrupulous about the details, took precautions—yet Bruno’s murder had scared them all. Made them wonder at the implications. Could it be . . . ? But a month passed and nothing. Were they safe?

Not totally safe, not until the final trust document was rubber-stamped tomorrow. But that was only a formality. Nothing would go wrong this late in the game. He knew that—they all did.

Yet why had he woken up shouting in his sleep last night? Why did Philbert’s dentures grind so at dinner, and why did Alain drink a whole bottle of wine himself?

Brown leaves gusted against his ankles. On his right a blurred Arc de Triomphe glowed like a painting on a postage stamp farther down the Champs-Élysées. He kept a brisk pace, got his blood flowing, warmed up. He was fit as a fiddle, his doctor said, his heart like that of a man twenty years younger. A couple passed, huddling together in the cold.

Walking under the barren trees by the Grand Palais, he became aware of footsteps behind him. The footsteps stopped when he did. But as he turned at the intersection in front of the zebra crossing, he saw no one.

Nerves. The light turned green. He crossed. Midway down the next block he heard the footsteps again. Turned.

“Who’s there?”

Only a dark hedgerow, shadows cast from trees. Unease prickled the hairs on his neck. He walked faster now, looking for a taxi. Silly, he lived two blocks away, but he never ignored a feeling like this. Each taxi passed with a red light crowning the roof: occupied.

Stupid—why hadn’t he taken the taxi with the others? Kept to their protocol of precautions? His meal, rich in cream, sat in his stomach like a dead weight.

Every time he heard the footsteps, he turned and saw no one.

Paranoid, or was he losing his mind? Or was the brandy heightening sensations and dulling his reflexes?

Then a taxi with a green light slowed. He waved it down. Thank God.

“Merci,” he said, shutting the taxi’s door, breathing heavily.

“I’m only supposed to stop at the taxi stand, monsieur.”

“Then I’ll make it worth your while in appreciation.”

He gave the address.

“But that’s only two blocks from here.”

“Consider your fare doubled, monsieur.”

The taxi pulled away from the curb. He asked the driver to close his window.

But the driver ignored him. And turned toward the river. Not the way home at all.

Ahead, streetlamps rimmed the quai, their globes of light reflecting yellow shimmers on the moving Seine. His heavy insides curdled.

“You’re going the wrong way.”

The taxi accelerated, throwing him against the back of the seat.

“Stop.” He tried the handle. Locked.

Afraid now, he pounded the plastic partition and tried reaching for the driver’s shoulder. The wheels rumbled down a cobblestoned ramp.

“Let me out.”

He didn’t even realize where they were until the taxi stopped. The taxi had lurched to a halt below the Pont des Invalides, nestled in the shadow of its arch support. Mist floated over the Seine, the gurgling water swollen by early November rain.

And then the door opened and before he could defend himself, his arms were pulled behind him. “Take my money, just take what you want.”

“You know what’s going to happen, don’t you?” said a voice.

He gasped. “Please, let me go.”

“Don’t you remember the river?”

Panic flooded him. “Non, non. You must understand—it wasn’t supposed to happen . . . We can make it right.”

“Liar. Payback time.”

A rag was stuffed into his screaming mouth. His bile rose and all the rich food lodged in his gullet, choking him.

“You remember, don’t you? It’s your turn now.”

He was shoved to the edge of the quai and down into a squat. Through his blinding terror he saw one of his shoes fall into the water below. The lapping waves from a receding barge and the faint rhythm of faraway car horns masked his cry of pain. Even the lit globes of the sodium lamps faded into the mist on the cloud-blanketed night.

“How does it feel?” a voice hissed.

But he couldn’t answer as the sour-tasting gag tightened across his mouth. His tied hands gripped and flailed. He couldn’t breathe.

It wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

The shot to the back of his head was muffled by the plastic Vichy bottle used as a silencer and the rumble of the traffic overhead.